Evidence given by senior officers at the Taylor Inquiry

- The Taylor Inquiry was set up to establish what happened during the disaster and its causes, with a view to learning lessons that could prevent such events from happening again. It was a departmental inquiry, rather than a statutory public inquiry, meaning it was not a court, or course of public justice, and did not operate in that way. Unlike at a criminal trial, witnesses did not have to swear an oath before they gave evidence.

- Nonetheless, in his opening speech, Mr Collins, Counsel to the Inquiry, set out a “hope that all who are involved in this Inquiry appreciate it is vital that an accurate account be given even if that involves admissions of errors.” He added that “the avoidance of any such disaster in the future is more important than the justification for what occurred on this occasion.”

- In total, 60 SYP officers were called to give evidence to the Taylor Inquiry, ranging from PCs who had been on duty at the Leppings Lane end to senior officers. This meant that SYP accounted for more than a third of all the witnesses called.

- Concerns have repeatedly been raised about the accuracy and completeness of the evidence some of these officers gave. As set out at the start of this chapter, the Taylor Interim Report expressed the view that senior officers had been “evasive and defensive” in their evidence. It further stated that the quality of the evidence given by police officers “was in inverse proportion to their rank”.

- The focus of the IOPC’s investigation was around the accuracy of the evidence and whether any officer sought to deliberately mislead the Taylor Inquiry. In particular, the IOPC looked at the evidence that senior officers gave in relation to two broad topics: supporters’ behaviour and police tactics and actions to control the supporters.

- Investigators identified a high degree of consistency in the evidence senior officers gave to the Taylor Inquiry in relation to whether:

- SYP was responsible for monitoring the fullness of the pens

- SYP had previously closed the tunnel leading from the concourse at the Leppings Lane end to the centre pens of the West Terrace (Pens 3 and 4)

- SYP had previously deployed cordons of officers on the approach to the Leppings Lane entrance to check supporters had valid tickets for the game

- However, when some junior officers gave evidence, they offered different perspectives; some described previous police actions to close the central tunnel, including at the 1988 FA Cup Semi-Final at Hillsborough Stadium.

- The evidence the senior officers gave appeared to contradict what they had said in internal meetings.

- For example, as set out at paragraph 10.21, at the meeting on 26 April, Ch Supt Mole stated that there was a known contingency among senior officers to close the tunnel when the pens were full. He was the first SYP officer to give evidence to the Taylor Inquiry on 24 May. He was asked about the tunnel closure at the 1988 Semi-Final, where he had been match commander, but said: “I have no recollection of closing the tunnel in 1988.” In reply to further questions, he then stated: “I have no information of anyone putting a serial or barrier across that tunnel.”

- This prompted Lord Justice Taylor to intervene and ask: “You are saying nobody closed off the tunnel in 1988?” Ch Supt Mole replied: “I am aware of that suggestion, and I have made enquiries and can find no confirmation of that. I certainly have no recollection, and those Officers who were present have no recollection of it.”

- By the time Ch Supt Mole gave evidence, SYP had recorded on its HOLMES database a significant number of officer accounts that had mentioned the tunnel being closed at the 1988 Semi-Final. References to tunnel closure had been removed from some accounts by this date. This calls into question the extent and rigour of the enquiries Ch Supt Mole claimed to have made about the issue.

- When he gave evidence to the Taylor Inquiry, Supt Greenwood was asked how he would respond to the centre pens of the West Terrace becoming full. He suggested he would have simply alerted the PCB and stated: “I did not know of the arrangement in terms of what would happen if they got full.” He was then asked if he had any idea what action he would have expected to be taken as a result. He replied: “No, because we had never reached that stage.”

- However, a range of evidence shows that both before and after the disaster, Supt Greenwood drew colleagues’ attention to the crushing incident on the West Terrace at the 1981 FA Cup Semi-Final at Hillsborough Stadium.

- In his evidence on 31 May and 1 June 1989, Supt Murray was asked whether he had thought it would be necessary to block the tunnel when Gate C was opened on the day of the disaster, allowing large numbers of supporters in over a short space of time. He said he never considered it and denied any knowledge of the tunnel being closed at the 1988 Semi-Final.

- Supt Murray was asked whether any officers “were concerned to keep a watch on the filling of Pens 3 and 4 of the Leppings Lane terrace?” He replied: “There was no one who had a specific duty as such.” He was not asked directly what his own duties regarding the filling of the pens were.

- Insp White was on duty on the inner concourse at the Leppings Lane end, a role he had performed many times before. At the Goldring Inquests, he recalled that when he received a copy of the Operational Order for the 1989 Semi-Final, he had gone to see Supt Murray. He said that Supt Murray told him that he should not follow the approach he had previously taken to filling the pens in a sequential fashion and instead should leave all pens open and allow supporters to find their own level. He added that Supt Murray said “that he, up in the control box, was in the best position to see if anything was developing in those pens.” Insp White repeated this point twice more in his evidence.

- Ch Supt Mole, Supt Greenwood and Supt Murray were all highly experienced officers, who had worked at Hillsborough Stadium many times, at high-profile and ordinary matches. Yet when giving evidence to the Taylor Inquiry, they broadly indicated that the police had no responsibility for monitoring the pens and were either evasive in answering questions about past practice to close the tunnel or flatly denied any knowledge of it having taken place in 1988.

- This denial or omission appears to echo the removal of references to tunnel closure from the SYP proof of evidence submitted to the Taylor Inquiry and from SYP officers’ accounts.

- If these senior officers had acknowledged that SYP had previously closed the tunnel when the pens were full, it may have indicated a significant failure on the day of the disaster: the failure to follow past practice and prevent supporters from entering full pens.

- It was therefore of considerable significance when some more junior SYP officers giving evidence to the Taylor Inquiry described precisely the practice of closing the tunnel—echoing the evidence that had been given by some supporters. On 5 June 1989, Ch Insp Creaser, another officer with a lot of experience policing matches at the stadium, stated that he believed the tunnel had been closed at the 1988 Semi-Final. He later explained that though he had not been involved on that occasion, there were “several times when I have taken that action”, including at the 1987 FA Cup Semi-Final.

- Ch Insp Creaser also told the Taylor Inquiry that the reason he knew the tunnel had been closed at the 1988 Semi-Final was because he had “seen sight of a statement of a former Sergeant Higgins” which mentioned this. This referred to Police Sergeant Trevor Higgins (PS Higgins).

- The Taylor Inquiry team had not seen the account of PS Higgins but requested to. Over a month later, on 7 July, a member of the team reminded Hammond Suddards that the account had still not been provided. Documents show that the account was sent to Hammonds Suddards for review on 9 June and returned with suggested amendments on 12 June. There were then two further reminders from the Taylor Inquiry team before the account was delivered on 12 July. Many other accounts were delivered to WMP and the Taylor Inquiry in this period.

- The evidence suggests that SYP did not forward the account of PS Higgins with due expediency. By the time it was delivered, the Taylor Inquiry was no longer hearing oral evidence, so there would have been no chance to call PS Higgins as a witness.

- Nonetheless, two other officers referred to previous tunnel closure in their evidence and a third account was read to the Taylor Inquiry, from a police constable who stated he had closed the tunnel at the 1988 game, following an instruction from another officer. However, the police constable could not remember who that officer was.

- Given this evidence, SYP’s legal representatives informed the Taylor Inquiry team that the force accepted that the tunnel had been closed in some way at the 1988 Semi-Final. However, in subsequent written submissions SYP maintained that the tunnel had been closed in 1988 by junior officers acting on their own initiative—not at the instruction of senior officers. This, SYP argued, explained why it had not been mentioned in the SYP Operational Order and why senior officers were not aware it had taken place.

- In his Interim Report, Lord Justice Taylor concluded that, given how full the centre pens were, “the tunnel should have been closed off whether gate C was to be opened or not. The exercise was a simple one and had been carried out in 1988.” However, he commented: “Unfortunately, the 1988 closure seems to have been unknown to the senior officers on duty at the time.”

Several supporters who had been at the 1988 Semi-Final gave evidence to the Taylor Inquiry that in 1988 SYP had deployed cordons of officers, some distance from the Leppings Lane turnstiles, to check that supporters had tickets. Those who did not have tickets were turned away. According to the evidence given by supporters, this process:

- prevented those without tickets from approaching the turnstiles—thus reducing the total number of people in the turnstile area

- controlled the flow of supporters down Leppings Lane

Therefore, the use of cordons helped avoid a build-up outside the turnstiles. Some supporters said that they were surprised not to see cordons in place at the 1989 game.

- This was supported by the evidence of an assessor employed by the FA, who told the Taylor Inquiry that at the 1988 Semi-Final he saw police officers checking tickets at two points. When asked if this had been “a formal system of filtering people”, he said he was not certain.

- Ch Supt Mole was asked about this issue, including by Lord Justice Taylor, who pointed out that there was a good deal of evidence that supporters had been asked to produce their tickets in 1988. Ch Supt Mole suggested this was simply a by-product of the fact that there had been a steady flow of supporters towards the turnstiles, which allowed officers to ask people for tickets. He stated: “that might be the misperception that someone has of what was taking place.”

- Both ACC Jackson and Supt Marshall suggested at the Taylor Inquiry that operating a cordon system would be difficult. Supt Marshall told the Taylor Inquiry that “an enormously strong Police presence” would have been required to filter the crowd effectively on Leppings Lane.

- ACC Jackson stated: “I mean what you would require in a situation like that is certainly several hundred Police Officers to try and form some cordon to prevent the people crushing up to the turnstiles.”

- This comment was strikingly similar to the wording that had been agreed as an “appropriate answer” at a meeting between Mr Metcalf and ACC Jackson, Ch Supt Duckenfield and Supt Murray on 22 May. This meeting had been set up to talk through the “main points of criticism”.

- In relation to the use of police cordons outside the ground, the appropriate answer developed at the meeting was: “To have had any effect on the chaos which developed at Leppings Lane, something like 400 more Officers would have been needed, with a view to forming impenetrable cordons to block off both ends of the Lane and to send out sallies of Officers to disperse the crowds.”

- Another appropriate answer agreed at the meeting was that the arrival of supporters en masse would have reduced the potential effectiveness of cordons: “Any action taken to filter or slow down the movements of the crowds would only have caused problems elsewhere. As it seems that some three to four thousand people arrived between 2.30 and 2.50p.m., if some sort of block had been put on to allow, say, only one thousand through, the other two thousand would have had to be either contained or dispersed, with consequent nuisance and problems to local residents or even with the possible consequence of their moving down Pennistone [sic] Road, to confront supporters of Nottingham Forest.”

- In his evidence to the Taylor Inquiry, ACC Jackson stated: “From what I could see, they arrived in the last fifteen minutes, about 4,000 people.” This number had not been cited in his initial written account. In response to a subsequent question, he added: “the situation in Leppings Lane would be extremely difficult because of the topography and the residents. You would start pushing the crowd then back on to the main road, back into the residential area, and probably back to the flashpoint, I should imagine, where Notts Forest fans were coming.”

- ACC Jackson stated at the Goldring Inquests that he was in the Directors’ Box at the stadium by 2.40pm. The Directors’ Box did not offer a view of outside the stadium. It is therefore not clear how he could have seen the situation outside the Leppings Lane entrance in the last 15 minutes before the game, when he claimed he saw 4,000 supporters arriving.

- The meeting at which the appropriate answers were agreed was one of various occasions where SYP officers received support from the legal team, before they gave evidence to the Taylor Inquiry. Part of the stated reason for this was that a public inquiry was unfamiliar territory for police officers who were accustomed to criminal trials.

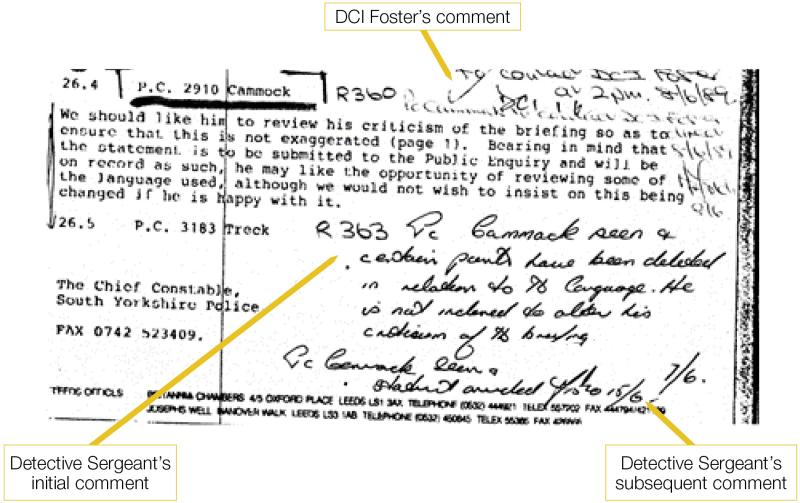

- It is normal procedure for officers to receive some support and preparation before cross-examination. Solicitors or more senior officers might advise them of questions they may be asked and identify potential issues or discrepancies in their evidence. However, the evidence set out by the IOPC suggests that SYP’s preparation for the Taylor Inquiry went further than this, with senior officers and a member of the legal team preparing and agreeing “appropriate answers” to likely criticisms. In one instance, this resulted in a witness using an appropriate answer as the basis for his evidence to the Taylor Inquiry, even though other evidence tends to indicate he would not have been able to give that account from his own personal experience.

- The Taylor Inquiry was not a court. There was no legal requirement for officers, or any other witnesses, to provide the whole truth, as long as they did not mislead. Therefore, there was no bar to the use of agreed appropriate answers, as long as these answers were not inaccurate or misleading.

- Nonetheless, it was certainly contrary to the spirit of the Taylor Inquiry and its intent and could be seen as an attempt to limit the evidence SYP put forward to the Inquiry.