Limited scope of WMP’s criminal investigation

- The fact that this was a criminal investigation meant that, unlike when it was supporting the public inquiry, WMP was now back on familiar territory. It had a team of officers with extensive experience in complex and high-profile criminal investigations. They therefore should have been well aware of what would be required from a criminal investigation. The Taylor Interim Report had provided a clear starting point in terms of lines of enquiry, and WMP had a large volume of evidence and information to draw on. This included thousands of statements and questionnaires, the accounts of SYP officers, reports from the HSE, and its own analysis and reports conducted for the Taylor Inquiry.

- On 6 September 1989, D Supt Taylor sent ACC Jones a memo setting out anticipated resource requirements and key tasks for the criminal investigation. These included:

- converting officers’ recollections into CJA statements

- questioning those with some degree of culpability

- interviews of new witnesses

- reinterviews of witnesses and police officers

- He suggested the number of WMP officers that might be required for each task.

- The task of converting officers’ recollections into CJA statements had also been cited by ACC Jones during his negotiations concerning the costs of the investigation.

- However, none of these tasks was undertaken. In fact, the scope of WMP’s criminal investigation was extremely and inexplicably limited. It effectively ended on 31 March 1990, with the submission of the file of evidence to the DPP.

- This submission date appears to have been decided by WMP alone. The IOPC has found no evidence that there was any request from any other party to complete the investigation by that date. In fact, it was slightly later than ACC Jones had initially envisaged; several policy book entries show that WMP’s aim had been to complete the investigation by the end of February.

- This was a very compressed timetable for a major manslaughter investigation, and no explanation has ever been given for why the timetable was fixed in this way. CC Dear specifically stated to the IOPC that he was not aware of any time pressure.

- During the six months from the end of September 1989 up until 31 March 1990, just 168 actions were raised in relation to lines of enquiry that were specifically undertaken as part of the criminal investigation. Of these 168, 92 resulted in no further action being taken—meaning that during this time period, WMP completed just 76 actions related to lines of enquiry for the criminal investigation.

- By way of contrast, across the same period, WMP undertook around 1,000 actions in support of the Popper Inquests and 194 related to investigating complaints against the police.

- It is also worth noting that 45 of the actions considered as part of the criminal investigation were related to supporter behaviour. Although 40 of these resulted in no further action being taken, the figure stands in marked contrast to the number of actions centred on the opening of the gates at the Leppings Lane end: 10.

- While there is evidence that supporters were considered a subject for investigation, the main offence being investigated was manslaughter, and the opening of the gates had been identified in the Taylor Interim Report as a critical moment. Further, the Taylor Interim Report had noted that failing to close the tunnel to the centre pens, when the gates were opened, had been a critical error.

- The fact that the tunnel had been closed on previous occasions but was not closed on the day of the disaster was accepted by all parties, including SYP. However, as discussed in chapter 11, several of the most senior SYP officers on duty had given evidence to the effect that they were either unaware that the tunnel had been closed previously or had only become aware of it following the disaster. They suggested that the tunnel had been closed by junior officers, acting on their own initiative.

- A large amount of oral evidence given to the Taylor Inquiry had indicated that tunnel closure may have been a more common occurrence or even a formal police tactic. Furthermore, a number of officer recollections submitted to WMP indicated that the action had previously been carried out on the instruction of more senior officers.

- In the context of an investigation into the possible offence of manslaughter by gross negligence, this issue was of considerable significance. If evidence was found to demonstrate that:

- closing the tunnel was an accepted SYP tactic to prevent overcrowding in the pens, and

- that officers in the PCB were aware of this tactic

then the failure to implement that tactic could have been deemed an indicator of negligence.

- It would have been a logical and appropriate investigative step to interview each of the officers who had given evidence about this, to seek to verify their accounts and ascertain what their understanding of the police tactic was. However, the IOPC has found no evidence to suggest WMP made any effort to contact them again. Instead, actions were raised to ask some officers that had been on duty at the 1988 Semi-Final about their knowledge of any action to close the tunnel on that occasion. These did not result in further information.

- Of the 168 actions for the criminal investigation, three were recorded as high priority. Two of these involved taking statements from a married couple who had not been at the match. They had travelled from Manchester Airport on the M62 towards Sheffield, on the way home to Wakefield in West Yorkshire, on the day of the disaster. This meant they had taken a similar route to some Liverpool supporters on the way to the match.

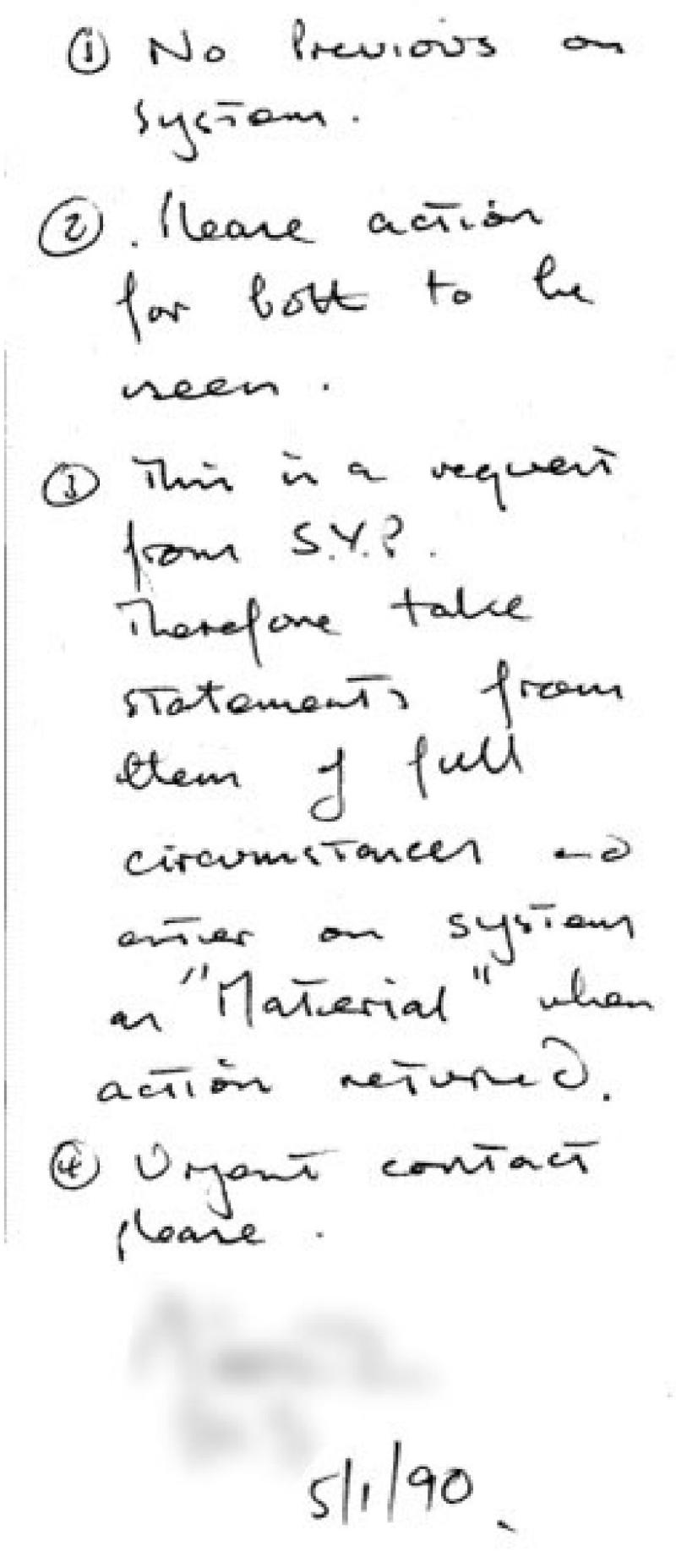

- An instruction from D Ch Supt Foster shows that WMP took statements from these two individuals at the request of SYP.

Figure 15A: Note from D Ch Supt Foster, 5 January 1990 (Source: SYP Archive)

- The statements were obtained within a week and were very similar in their wording. In particular, both stated: “I was disgusted by the conduct of the football fans, the fact that they had been drinking and were urinating at the side of the road, in full view of other road users.” Both were included in the file WMP submitted to the DPP in March 1990.

- In 2016, the wife gave a statement to Operation Resolve. With regard to the allegations made about supporters, she stated she could “no longer recall much of their behaviour. I no longer recall seeing fans urinating in public places.”

- It is notable that WMP acted so promptly to obtain these statements—especially given the very small number of actions raised during its criminal investigation. It is also striking that D Ch Supt Foster determined that the information these witnesses could give was “material” before it had been gathered.

- Conversely, the IOPC has identified 37 potentially key witnesses that WMP did not approach or take statements from as part of its criminal investigation. As well as some police officers who may have been able to provide vital additional information, such as those in the PCB, WMP did not take statements from SWFC officials, or Eastwood & Partners or SCC employees. All three of these organisations were under investigation for possible manslaughter.

- SWFC officials could also potentially have been investigated for health and safety offences; Operation Resolve secured the conviction of Mr Mackrell (SWFC Club Secretary) for offences involving health and safety legislation, almost entirely on the same evidence available to WMP. The HSE had advised the Taylor Inquiry that there had been a repeated failure to adhere to the Green Guide and potential failure to meet obligations under the SSGA 1975. However, at the start of the criminal investigation, the HSE informed ACC Jones that it viewed the issues around the disaster as not falling under its prosecutorial remit. Despite this. the evidence indicates WMP gave little or no consideration to such offences.

- Even though some senior SYP officers were identified early on as suspects in the manslaughter investigation, WMP chose not to interview them under caution before submitting its file of evidence. This was a highly unusual decision.

- Altogether, this meant that during its criminal investigation, WMP did not substantially add to the evidence that had been presented to the Taylor Inquiry. In a letter to the Taylor Inquiry team in October 1989, ACC Jones acknowledged this, commenting: “You will see, apart from the provision of more detail and improved identifications of the deceased, nothing new has emerged.” He reiterated this in conversation with the Secretary of the Taylor Inquiry team in December 1989. However, in the file it submitted to the DPP, WMP appeared to reach a very different view of that evidence.