The failure of the Casualty Bureau

- Throughout this period, SYP’s Casualty Bureau was operating. It was opened to the public at 4.23pm. As set out in the SYP Major Incident Manual, it should have been the single point of contact to help families and friends seeking their loved ones, by gathering, processing and providing accurate information about those involved. However, almost from the moment the telephone lines opened, it was overwhelmed by the volume of calls.

- With thousands of supporters at the match, thousands of families were anxiously seeking news. The only ways that those at home could gather information about the wellbeing of their loved ones were if someone in Sheffield telephoned them, or through the Casualty Bureau.

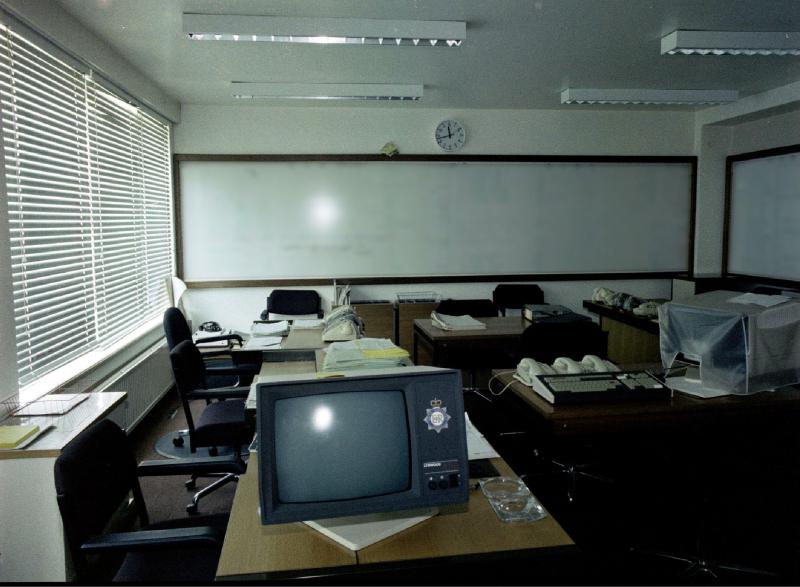

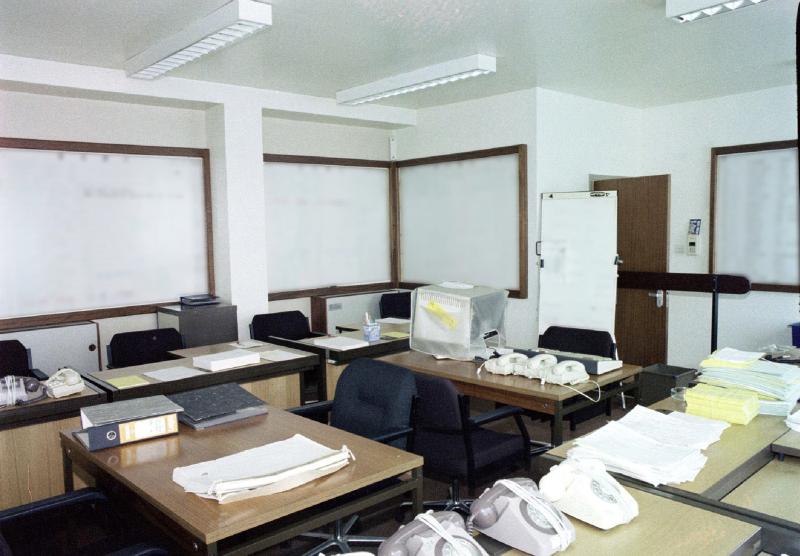

- Given this, the Casualty Bureau—a room in the SYP training centre at Ecclesfield Police Station in Sheffield—was clearly too small. Figures 6B and 6C show the set-up at the time. There were eight telephones: four were dedicated for internal use and contact with the gymnasium, the hospitals and other sites. The other four were allocated to receiving calls from members of the public. It also had two direct links with Force HQ. The desks were close to each other, so there would have been limited space for privacy and conversations would have been overheard.

Figure 6B: View of SYP Casualty Bureau, 1989 (Source: SYP)

- At the point it opened, the Casualty Bureau had no records of casualties and almost no information to give to callers. The call handlers had received minimal details from the ground, even though the setup of the Casualty Bureau had begun following an instruction from ACC Jackson at 3.17pm.

- Staff took the personal details of the callers and the names and descriptions of the people they were enquiring about. Information was handwritten on casualty enquiry forms, with the intention that this could be matched with information received from the gymnasium or hospitals. Names and ages of those missing were then also written on whiteboards on the walls of the Casualty Bureau, so that they could easily be seen by fellow call handlers. However, the number of missing people was so high that the call handlers ran out of space and had to use the blinds in the room as additional whiteboards.

- When additional staff were drafted in, they had to sit in a different room and could not see the whiteboards. In some cases, this led to the creation of duplicate records, which added to the overall confusion.

Figure 6C: View of SYP Casualty Bureau, 1989 (Source: SYP)

- A further problem quickly occurred. The intention was that the Casualty Bureau should have separate telephone numbers for the public and internal use. However, when the telephone number for the public was released, the internal ones were too. This resulted in all lines being available to members of the public. With large numbers of incoming calls at all times, officers at the hospitals found it virtually impossible to contact the Casualty Bureau with details of casualties. Operation Resolve has not been able to establish who released the numbers, or how it happened.

- Further, all of the telephones were on the same loop, which meant that when the Casualty Bureau number was called, all of the available phones rang simultaneously. This resulted in the phones ringing continually and there came a point when call takers left their phones off the hook to have time to complete their paperwork.

- Some of these issues had been identified in an SYP Casualty Bureau working party meeting in December 1987. For example, it had been decided that four phone lines were insufficient, and the minimum requirement should be ten lines. However, no action was taken in response to this, until 7pm on the evening of the disaster, when BT installed four more lines.

- A Casualty Bureau training exercise on 27 October 1988 had identified that installing a fax machine at a hospital provided better communication between the two sites. Yet fax machines were only installed several hours after the Casualty Bureau was opened.

- The Casualty Bureau had only ever been used in response to one live incident, on a much smaller scale, so many processes had not been tested. For example, the forms in use for recording information about casualties were slightly different in each location, meaning there was some duplication of effort, but also some details missed.

- Compared to some of the other issues identified in this chapter, the treatment of families and friends by the Casualty Bureau has been subject to few concerns or complaints. In the majority of cases, those who referred to attempting to contact the Casualty Bureau, or attempting to call the emergency numbers, have indicated that they either gave up trying to get through or that they received no useful information. As a result, they set out for Sheffield.

- The SYP Casualty Bureau was also responsible for contacting other police forces, including Merseyside Police, which had activated its own Casualty Bureau, to ask them to visit family members of those individuals who had been identified, either formally or provisionally, as having died.

- It sent out a series of messages, many of which were specific in their content and stipulated what response SYP required from the recipient police force. For example, there were requests to inform a named individual that a provisional identification had been made. In at least eight cases, the provisional identification had been made using details found on personal items such as rail passes, driving licences or other identification documents. A further six messages requested that a named individual should come to Sheffield “for the purpose of formal identification”.

- In some cases, SYP asked Merseyside Police to contact families even though other family members or friends had already identified their loved one. Operation Resolve has also established that on occasion the content of the message sent to another police force contained inaccuracies, which clearly had the potential to cause further distress and upset, beyond that already caused by the nature of the message. For example, one message sent to Merseyside asked for a woman to be visited to be notified of the death of her son; it was in fact her husband that had died. Further, a formal identification was still required.